(This is second part of my PiterPy talk adaptation, first part is available here)

Previously I described various ways AST could be used to alter Python language. Now I will concentrate on translation, and we will translate Python to JavaScript.

Translation

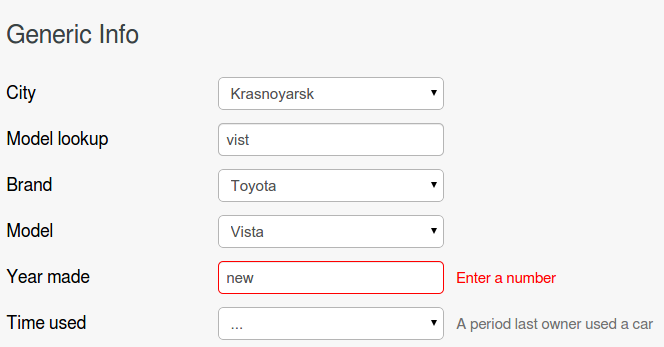

Unlike all Part 1 examples this one started from real need, the one as mundane as form validation:

Here we have a form with a validation error visible, we typically want this to be shown as soon as possible, so we implement these checks in browser in JavaScript. But we still need to check everything on the server to not let broken data into our database.

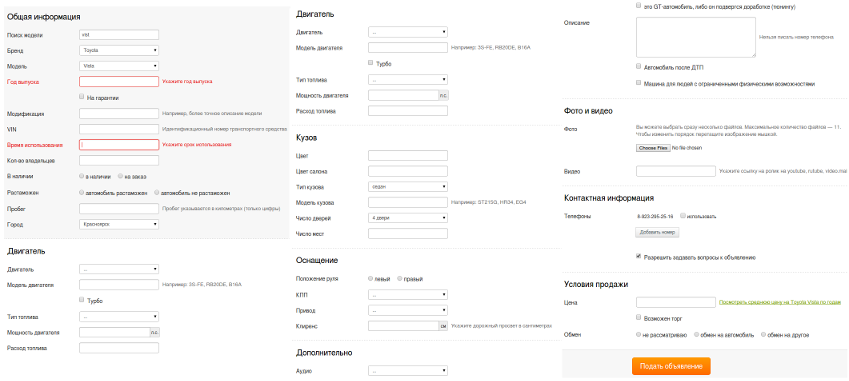

Usually we just duplicate logic and this works. Until we get many forms and all of them are like this:

When we arrive to this scale code duplication starts to cause problems duplication always does: some things are checked only in one place, some things are not updated accordingly and contradict each other. We show weird errors to our users and save broken data to our database.

In ideal world we wish to write every rule just once and then use it in both environments:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

So we naturally came to translation. We want to write validation in python, translate it to JavaScript and use on front-end automatically.

The Easy Part

Let’s start from something simple, like translating a plain lambda like this:

1

| |

We will use AST to for translation, so first we need to get it for this lambda. It’s hard to get source for lambda to parse it, so we’ll use meta library to decompile its bytecode:

1 2 3 | |

Once we do that we get a tree like this:

I simplified it to look prettier, but all significant aspects are still here.

The easiest way to render it to a new language is to start from leaves: numbers, variable names and operators mostly look the same in JavaScript. We will employ ast.NodeVisitor to walk the tree:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

After using this we come to:

When leaf nodes are done we can compile code for ones depending on them:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

And we’ve got to:

We can continue going up the tree and finally get:

1 2 3 | |

Yay! We did it. But…

Complications

What about translating code like:

1

| |

There is no chained comparisons in JavaScript, the best we can do is translating this to:

1

| |

There is also no not in operator in JavaScript, combining all that Compare translation complicates to (not necessary to read and understand all this, just appreciate the complication):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Another complication is keyword arguments and star arguments. We can deal with them by complecting our code even more or by refusing to handle this case at all:

1 2 3 4 | |

Now we are translating only subset of Python, but this should be okay since translation is not our goal, it’s code deduplication for validation rules. So as long as translator works for this particular use case we are fine.

Closures

We are still not done yet. We probably don’t want to write same validation rules over and over, so we will end with code like:

1 2 3 4 | |

It’s easy to see that limit in JavaScript code refers to non-existing variable. To fix that we need to introspect values enclosed within a function, thankfully Python introspection has our back:

1 2 3 | |

Here the closure is a tuple containing single cell with an int object in it. Makes sense since we are enclosing 50. It’s fairly easy to get cell contents:

1 2 3 | |

It’s also easy to introspect free variables refering to enclosed values:

1 2 | |

This co_freevars always have the same length and order as cells in closure, so we can pair them up and translate the whole thing to:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

So we’ve got a closure. This highlights how we are not really translating functions, but closures, which are functions plus context.

More Closures

Unfortunately func.__closure__ doesn’t capture everything, any global names and built-ins are still uncovered. Let’s translate this one:

1

| |

We can access function globals and built-ins namespaces with:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

So we only need to detect global names used by a function. We could have walked the AST, but then we would need to separate local and enclosed non-local names from global ones. The easier way is to introspect bytecode, which looks like this:

1 2 | |

Just a binary string, not that pretty. But python standard library provides us dis module to handle that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

The thing to see here is LOAD_GLOBAL instruction, it corresponds to global variable use. dis module only prints bytecode nicely, but doesn’t let us really in. So we go for another asset — byteplay:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

So we collected all refered global names, we can translate them unless they are implemented in C. To handle that we can supply a dict like:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

With code which doesn’t make sense in Python. However, it will make sense after translation:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Actually we could have used strings in BUILTINS dict, but with lambdas we can refer to other things in our implementations:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Which enables us to make things like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

Here all() is defined as a nested closure. Also the whole thing starts to look complex.

Fortunately we don’t need to write this, we don’t even need to read this, we only deal with

python lambdas. And that one is just a single line for the mess above:

1

| |

Meeting Halfway

We’ve already come a long way, however, some things still won’t work:

1 2 | |

To fix this we will need to write shims for all python types and convert everything before passing to our function. This sounds like a lot of work, so went another way — just don’t write like that, write this way instead:

1 2 | |

Look, system does many things to make everything work, now we can come along and finally meet halfway. This approach worked wonderfully for us, we managed to get practical solution with:

- no runtime,

- no shims,

- only 300 lines of code.

Compare this to full-blown python to js translator. Anyway let’s see what it have brought to us.

Demos

Here is how validation looks. It updates as we type and wholly executed in the browser:

And we don’t write any JavaScript to achieve that. We write this instead:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

This works both in browser and server-side so we don’t need to duplicate logic or messages. Also having lots of similar fields we can reuse everything: fields, predicates, cleanup functions, rules, which are just lambdas plus text messages. So it really looks like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

We can also employ inheritance:

1 2 | |

Computed Properties

We really got more from this system than just validation. And first thing to show is computed properties. These are visibility, labels, choices and more. I’ll demo it with another tiny screencast:

Here we can see several aspects — when user selects “exchange to a car” a new drop-down appears, and when a label changes depending on who pays extra. Here is how it looks in code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Additional benefit we get here is that we can compute visibility server-side and do 2 things: first, render a form in an appropriate state from the start (less flickering in the browser) and, second, discard any input we got from invisible fields automatically. Another example of additional benefit is calculated choices, able to get them on back-end we can check if value is one of them.

Other thing to note is that now we have dependencies, e.g. label text and visibility depends on exchange_terms field value. We could have added some tricky introspection, but we instead required programmers to specify dependencies explicitly:

1 2 3 4 | |

This is in line with our meeting halfway principle and it worked this time too.

Passing Data

The last demo for today will show how easily we can pass data to client. Here I show how field values could be automatically selected:

To look through car models we need to pass their list to browser and we can do this simply by enclosing data structure with a function:

1 2 3 4 | |

This lambda uses models so they are translated to JavaScripts array of arrays and passed along with function. This is very handy when, for example, creating chained selects and under many other circumstances.

The Bigger System

You probably already noticed that there is a bigger system besides translator here. These are all its parts:

- declarative descriptions of fields, models, forms, filters, listings and detail pages,

- translation of clean, validate and property compute functions,

- transparent data forwarding.

There is the thing with tools that when you introduce some new very useful one you get a whole lot of new possibilities, you can make much faster something that took ages previously or you can even do things, which were impossible before.

This also works for developer tools. Introduction of this system had led to a population boom — we’ve got from 7 forms to 51, and you can double that number ‘cause we also autogenerate filtering form for each of them. We also got to 500+ database tables. All of this without loosing our sanity or growing our code base to some insane LOC number.

Decency

In python world we have this stigma on metaprogramming. Like it’s dirty and should not be used in any serious setting. It’s true that this is a complex technique that brings its costs. But as any other consideration this has its limits.

By promoting reasonable considerations to emotional and even kind of religious level we loose an ability to judge it mindfully. We dismiss something even before considering it seriously. And doing so we miss great solutions.

This worked for us. What will do for you?